01

Poverty among smallholder farmers is a systems failure.

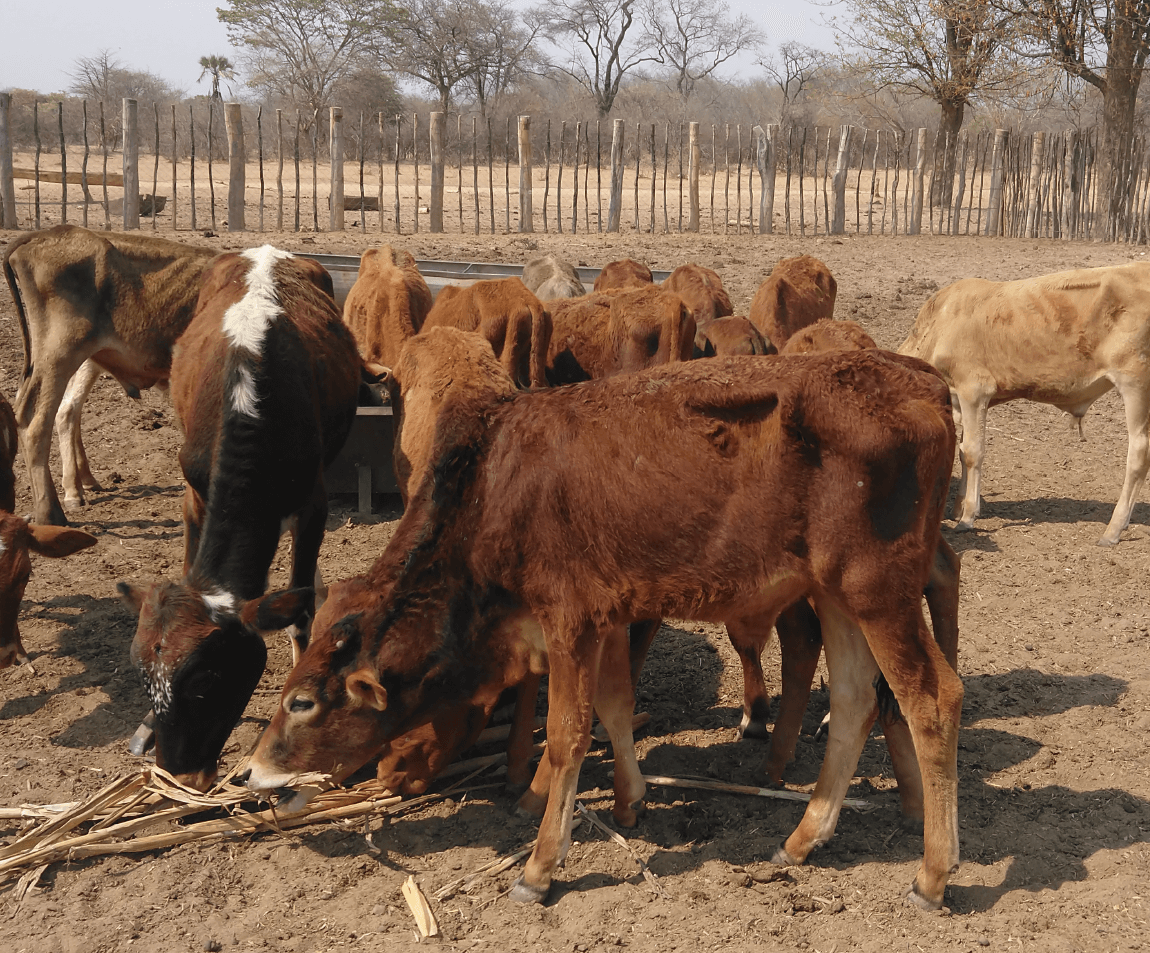

Across Zimbabwe and much of Southern Africa, smallholder farmers are central to food security, employment, and rural economies. Yet millions remain trapped in poverty, not because they lack effort, knowledge, or ambition, but because the systems around them do not work in their favour.

Smallholder farmers face persistent and interconnected constraints: unreliable markets, limited access to finance and services, climate variability, land and soil degradation, and weak coordination across value chains. These challenges reinforce one another, increasing risk and reducing farmers’ ability to invest, innovate, and plan for the future.

02

Why Poverty Persists in Rural Areas

Rural poverty is rarely caused by a single factor. It is the result of multiple, interacting failures:

- • Weak and exclusionary markets that do not reward small-scale producers fairly

- • Limited access to appropriate finance, inputs, and services, particularly in remote areas

- • Climate stress and environmental degradation that undermine productivity and resilience

- • Fragmented interventions that address symptoms rather than root causes

- • Low bargaining power and poor coordination among farmers and market actors

03

The Cost of Inaction

When these structural challenges go unaddressed:

- • Smallholder farmers remain locked into low-return, high-risk activities

- • Rural youth disengage from agriculture and local economies

- • Natural resources continue to degrade

- • Food systems become more fragile and less resilient to shocks

- • Poverty is transmitted from one generation to the next

04

Why a Different Approach Is Needed

Ending the indignity of poverty among smallholder farmers requires systemic change. Farmers need more than inputs or training; they need access to functioning markets, appropriate finance, resilient production systems, and locally rooted enterprises that can deliver services reliably.

This requires approaches that work across ecological, economic, and social dimensions, aligning incentives among farmers, private sector actors, institutions, and policies. Solutions must be designed to endure beyond individual projects and funding cycles.

05

Why Agroecology Matters

Addressing rural poverty requires recognising the close links between natural systems, livelihoods, markets, and power.

Agroecology provides a holistic framework for doing so. By working with natural processes, strengthening biodiversity, reducing dependence on external inputs, and valuing local knowledge alongside scientific evidence, agroecology helps smallholder farmers reduce risk and improve resilience. When combined with inclusive markets and enterprise development, agroecological approaches enable farmers to retain more value from their labour while restoring the natural resource base on which their livelihoods depend.

For Agricultural Partnerships for Transformation, agroecology is not a stand-alone activity. It is the lens through which we design interventions that restore dignity, build resilience, and create lasting pathways out of poverty.

APT’s Response

Agricultural Partnerships for Transformation was established to address these systemic challenges. We work to create the conditions in which smallholder farmers can earn dignified incomes, strengthen their resilience, and participate meaningfully in rural economies.

Rather than substituting for markets or institutions, APT works to make them work better — for farmers, for communities, and for the long term.